To the Desert and Back: Thoughts on Time, Space, and Life

I had the good fortune to spend the first week and a half of the year looking for fossils in Big Bend. Here's a little bit about what it's like to live in the desert.

First, we walk. From flat desert - sandy, gravelly soil, sparsely populated with mesquite, creosote, prickly pear, laria (like yucca on stilts), and angular cobbles of basalt - into the Late Cretaceous clays, banded gray and red. These are hell to walk on. When wet, they have the consistency of peanut butter, and you are soon dragging five pounds on each boot. With moisture, the clay expands like some radioactive horror in a 1950's sci-fi movie. Chunks of it in streambeds blossom cancerously like mutant cauliflower. Entire hillsides bubble up into an unholy confection we call popcorn.

When wet, the popcorn is slicker than snot on a glass door handle, and impossible to climb. As the moisture evaporates, the popcorn attains its eponymous texture, like a giant stale cake. With each step, your feet punch through a dry crust and sink into the soft labyrinth underneath, maybe only an inch or two, maybe twice that. Over the yards and miles, it takes its toll. Especially when you're climbing, which you often are. From the desert floor the popcorn hills at the rim of the basin look tame enough, lined up in neat receding rows like ships in a marina. Up close you find yourself lost in a fractal landscape of endless meandering gullies and washes. You don't have to go in very far before slogging up over the ridge into the next wash is more appealing than walking out of one wash and back up another. Also, if there is any breeze it will be blowing only on the ridges, not in the washes.

In January, with the last sips of last week's rain still cooking out of the ground, the air is not as fantastically dry as it is in Utah or Nevada in July, but it is still plenty dry. Lips crack and noses bleed. The sunlight doesn't help. I know, intellectually, that this is the same yellow main sequence star that shines on Oklahoma and California, but out here it seems like a different beast: closer, hotter, more penetrating, more indifferent to comfort or the continuance of life.

But - there are dinosaurs. Where the popcorn hills hit the desert floor they sit on broad fans of flat white sediment. Most of these fans are freckled with pebbles. Depending on location, these may be chunks of basalt, little blobs of sandstone--or fossils.

If you wanted sheer volume, you could sit down and fill a pail with chunks of bone in no time. You would be limited only by the speed with which you could pick it up. But you wouldn't learn much from your bucket of bones. These shattered chunks could be pieces of turtles or crocs or dinosaurs of every shape and size. We have no way of knowing which, so we pass them over without further thought, except perhaps to wonder at the apparent lunacy of ignoring or discarding actual fossils.

The bone shards so serve one important purpose, and that is to help us identify productive hills. Any place that has bone shards will also have real treasures, i.e., things we can identify: teeth, scales, scutes, armor, claws, horn cores, and even pieces of eggshell, from fish, amphibians, turtles, lizards, crocs, mammals, and dinosaurs. In general, this Cretaceous bric-a-brac is too small to be spotted or identified from more than one or two feet away. So we crawl across the clay pans on hands and knees, and sometimes on our stomachs, picking up a thousand pieces of rock and bone and saving from that perhaps fifty identifiable fossils. The good bits go in vials or ziplocs or little wads of toilet paper, and we keep crawling.

After a few days of sore knees and elbows, cracked fingers, painfully dry nostrils, slightly sunburned retinas and broiled skin, with a bag full of a billion or so turtle frags and perhaps only half a billion croc chunks, you may begin to doubt your sanity both locally - Am I crazy to be out here? - and globally - Am I going crazy, period?

Then you find something good. Real good. Amazing. A real live dinosaur tooth, so shiny and perfect it could have fallen out yesterday. Basking in the sure cool knowledge that you - you - are the first person to lay eyes on this gem after its tremendous voyage through time and rock, that this discovery for science and mankind, be it ever so petite, is yours and yours alone, you turn giddy. Suddenly all the privations of desert life seem like a small, or at least a reasonable, price to pay. For a while afterward, everything carries a little leftover charge and even the turtle frags seem exciting.

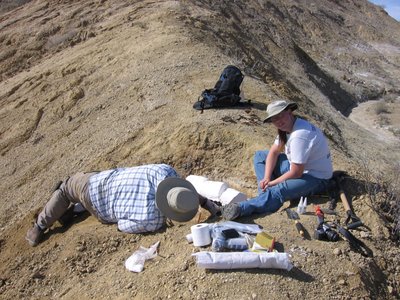

We also found a few big bones, and by we I mean they because that day I was off helping Bill and Mary Clark collect desert ants. But I was back the next day to help jacket and haul the big bones. The hardships and rewards of big bone paleontology are different from those of micropaleo but equal in magnitude (to me at least): sore arms from hours of hammer and chisel work, lots of sitting and laying in awkward positions in cramped holes on uncomfortable surfaces, hands, arms, and clothes crusted with moisture-leaching plaster, all set against the methodical, satisfying transformation of a real live dinosaur bone from a lump in the ground to a plaster-encased bullet of pure science, forged from thought, effort, and time.

Usually we had the last hour of each day off to go explore. Richard Peltier, a lanky young geologist from Sacramento, was my partner on these little expeditions. Officially we were looking for more fossil localities, and we did look, and we found a couple.

Privately, I just wanted to see some desert. I have always been drawn to open spaces, silence, human companionship measured out by the shot glass rather than the swimming pool, and to seeing what lies over the next hill. For me the desert is the perfect marriage of desire and object, and landscape that is clearly (often painfully) indifferent to my presence and well-being but that nevertheless seems to fit me, body and soul. I do not excel in speed, strength, or coordination. My eyesight is so-so even with glasses and my hearing is not great. About the only physical activity I excel at is not quitting. Fortunately the only thing the desert really demands is perseverance. I can do that.

So Richard and I would usually choose the tallest thing nearby that was attainable given our time constraints, trudge to the top, and spend a little while taking pictures, having a snack, and drinking in the vista. The march back was more leisurely, with plenty of diversions to interesting rocks or plants or whatever. The desert is only desolate in the broad view. Up close it is just about jam-packed with marvels to delight the eye, hand, and mind:

bleached remains of land snails and millipedes...

hills capped with slowly shattering sandstone...

animal tracks...

burrows...

fossil oysters...

petrified wood...

weird rocks...

coal-dark layers of lignified clay...

mysterious scat...

bizarre plants...

exotic critters...

odd landforms...

Hanging over it all is a silence so vast and absolute that it would seem like an abomination to break it, were it not so swiftly mended.

I am sitting on top of a mountain--well, a foothill, really, though it felt like a mountain to my legs. My butt is perched on a block of basalt, remnant of an ancient lava flow that covered this whole area from horizon to horizon. My feet are in sandstone, layed down by a river near an ocean that swarmed with reptiles the size of SUVs. At the limit of my vision are a few miniscule figures on the distant popcorn, remote from me in distance, elevation, personal and geologic time, and inclination: the other members of the team, who have chosen to spend their free hour on the flats. All save Richard, who has the gift of speaking concisely and engagingly and also of knowing when not to. United by our mutual reliance and the shared experience of the climb, separated by twenty feet and an unenforced but mutually agreeable silence, we are together but alone with our thoughts.

I love this place. I love the space and light and distance. I love the daytime heat and nighttime cold (29 degrees when I crawled out of my iced over tent this morning), the dryness and difficult terrain and hostile vegetation, both for their own sakes and because they keep away most everyone else. Big Bend is far from anywhere, tucked into a corner of the nation, distant from any major airport or interstate highway. There are no drive-thru tourists here. The handful of people we have encountered in the park's 800,000 acres were also drawn here not because it is easy but because it is hard.

One under-appreciated side effect of technological advance is that it gives us new metaphors to crystallize previously elusive thoughts. The gleam in NASA's eye is the orbital skyhook or space elevator, a cable of industrial diamond and buckytubes that would stretch from ground to orbit and allow us to haul stuff up to space like a fisherman reeling in a bass.

I love the desert, but this voyage in time and space has carried me far away from Vicki and London. The knowledge that they are so far away drags at me, not like an anchor, but like a skyhook. Not down, but up. My hearts strains against the sinews that hold it in my chest, struggling to burst into the air and hurl me across the long hours and miles to my family, to the people to whom I belong. I ache for the emptiness around me, so recently attained and so soon to be lost, and for the emptiness in my arms at breakfast and bedtime, which has now lasted for half of forever and will not end, it seems, until the other half has run out.

Time flows on at its same old pace. With no options and nothing better to do, I savor this two-edged ache. It ties me to the earth, to the passage of time, to the continuity of the human race, in which I am now embedded, having both ancestors and offspring.

To want a child and not be able to have one is a terrible sentence. Vicki and I languished in that prison for a long time. Then, when hope had almost run out, we found out that we were pregnant at last, and after all.

A few years ago a friend got married and did not want to fly on her honeymoon. I asked her why not. She said that after a long string of misfortunes and years of struggle on slight resources and slighter hope, everything had turned around: a good job, a clean safe solid house, child off to college on an unexpected scholarship, and finally, a good man, intense but unhurried courtship, a ring, and a wedding--after all that, after such an unimaginable run of good fortune, she was afraid that God was about to drop the other shoe.

That's how you feel the morning you find out that you are finally going to have a baby. All debts squared, all prayers answered, you have nothing more to ask and just want to get away clean. But you can't. Out of the frying pan and into the fire, now you lay awake worrying about miscarriage, birth defects, extra chromosomes, missing pieces...once more you are deep in the red at the Cosmic Bank of Karma and Heavenly Blessings. Then the baby comes out okay and you worry about SIDS, drops, falls, stairs, chairs, cars, etc., etc., each threat in its season, and it never ends. Through it all you do the only things you can: watch and pray and hope.

And then one day, shockingly, you realize that this is how your parents felt, and feel, about you. This is the beginning of wisdom.

I am 31. Half of you are wondering how a 31-year-old can have anything interesting to say yet, and the other half are marveling that I can still string words together in such an advanced state of decrepitude. Hold on, though, I'm getting to that. Up to the age of 29, I felt like I was 18, or perhaps 22. My outer circumstances changed somewhat during my 20s, but basically by their end I felt like the same 20-year-old I'd always been (hadn't I?), just a little older. I was outside the flow of time. No really, of course. Better to say that I was not cognizant of the flow of time. Time passed, stuff happened, but the time and the stuff slid over my mind like cold water over a smooth rock.

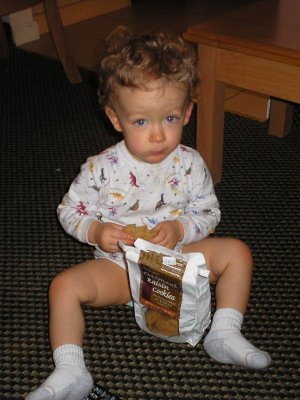

Now, though, my clock is ticking. No more coasting, no more loafing. I can't help but be aware of it, this little clock, object and focus of my life, with his smiles and rolling over and crawling and walking and even, just this week, saying "I yuv you" (--ouch, it hurts even to write, this cocktail of pride and pain). I am embedded in the flow of time, in the chain of life. He is my anchor to the earth and my skyhook to the heavens, my sundial and time machine and crystal ball, my student and my teacher, my playmate, my temple, my homeland, my home.

I hope that as the years carry us together and apart and together again that I will have the wisdom and the strength to walk before him when needs me, beside him when he'll let me, and above all to let him run ahead as often as I can--to find the golden mean between holding him close and letting him go.

Being a parent is a long exercise in being pulled apart, in carrying your heart outside your body, in knowing that things are going to hurt and doing them anyway. It is the most courageous, demanding, terrifying, fulfilling, necessary, and noble thing in life. It is life. And I am thankful for it--for him--every day.

------

Photos with Rich or Vanessa in the filename were taken by Richard Peltier and Vanessa Meredith. Thanks, guys. Loads of Christmas pictures coming soon.